James M. Flammang, author of 30 books (including

six for children), is at work on several more,

including the title described below.

An independent journalist since the 1980s, Flammang

specialized in the automobile business. During

2016, he turned away from cars and into more vital

topics: work/labor, consumer concerns, and especially,

the emerging outrages of the Trump administration. His

website, Tirekicking Today (tirekick.com) has been

online since 1995.

Steering Toward Oblivion

The Automotive Assault on American Culture

by James M. Flammang

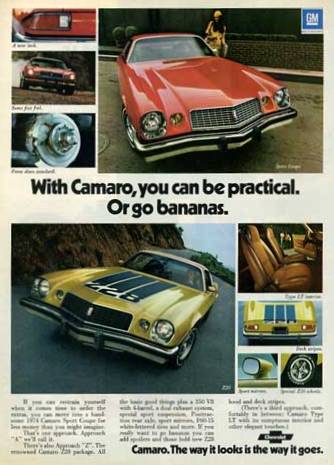

Advertising that pushed big, powerful cars (and later, SUVs)

helped make the automobile a centerpiece of American society.

Chapter Outline

Introduction:

Expanding upon material described in the Overview, this several-page Introduction will explain what Steering Toward Oblivion is about, who I am, why I have written it, and how I hope readers will react. From the beginning, I intend to keep the tone light and breezy, to demonstrate that readers need not fret about the possibility of a heavy-handed approach in the chapters that follow. I intend to explain briefly that the text is divided into three sections, because the media, marketers, and individual motorists all have played substantial roles in the development of the car culture and its impact, both good and bad, upon society. The Introduction concludes with the latest details of the shrinkage and potential collapse of the domestic automobile business, and the current state of our car-dominated culture.

Section I

Media: Conveying the Automotive Message

Chapter 1: Party Time - complete with presents

Lavish media programs, held all over the U.S. (and the world), draw serious journalists and hangers-on alike, to show off the virtues of the latest car models. This chapter describes some typical events, chronicling what happens from the day the invitation arrives, through the driving day, up to departure from the luxury resort or hotel.

Cozy relationships abound at these programs. While many journalists evaluate vehicles and their makers with objectivity and lack of bias, others rarely or never meet a car they don't like. That's partly because most auto writers are enthusiasts. Lack of objectivity and excessively-friendly ties to automakers are among the serious issues addressed in this chapter.

Chapter 2: Unnatural Selection - Access Denied!

Several hundred U.S. journalists attend out-of-town media launch programs at least occasionally, but automakers decide who should be there and who will be excluded. Many invited guests are part-timers rather than full-time professionals. Those who struggle to earn a living from writing about cars must compete against those who have other jobs or are retired - who don't need the income, but remain active largely so they can continue to enjoy the traveling-journalist lifestyle. Recognized journalists also regularly receive new cars for week-long test-drives, from manufacturer press fleets.

Those covering today's auto business range from well-informed scribes to independent web-site operators and bloggers. Automotive publications date back to the beginning of the industry, but vehicle reviews came later. Today, in addition to professionally-prepared reviews in newspapers, magazines and buying guides, the Internet is overloaded with automotive material - much of it valuable but some demonstrating doubtful accuracy and little objectivity. Meanwhile, bloggers issue millions of words on the subject of cars, typically biased and excessively personalized. This chapters concludes by considering the shrinkage of media programs, as the domestic automakers strain to remain financially afloat.

Chapter 3: Critics of the Past

By the 1950s, social critics such as John Keats and Vance Packard were issuing harsh words about the automobile culture. As the consumer movement grew in the 1960s, Ralph Nader leaped into the forefront: the first of a series of zealous scolds, whose words were often deemed inconsequential because they obviously hated cars and lacked humor. In recent years, the laudatory words of enthusiast-journalists have vastly outnumbered those of any critics. Those who point out flaws in the automotive picture can expect to receive at least as much scorn as praise, from much of the media as well as from ardent motorists.Section II

Marketing and PR: Pushing Hard on the Automobilist Message

Chapter 4: Marketing Methodology

For more than 80 years, the auto industry has not only been trying to sell cars, but endeavoring to create a total automotive culture. This chapter chronicles the development of automobile marketing, including advertising and promotional methods. Along the way, we cite particularly egregious examples of ads and promotions that have sent dubious messages to the more gullible (usually young) motoring public. They began in the 1950s and early 1960s, as the "muscle car" emerged. Today's TV commercials are packed with jarring, rapid-fire scenes of vehicles careening into parking spots, roaring down blissfully vacant roads at startling speeds, and in some cases, flagrantly threatening the surrounding populace.

Public relations comes in for a healthy share of attention. This chapter looks at the other side of the media/public-relations coin, dissecting the activities of PR operatives and observing their relationships to journalists, which mix flattery and friendliness with providing useful information and contact with important industry executives.

Chapter 5: Image and Demographics/Psychographics

Serious study of automobile shoppers and customers arose in the 1950s, especially with the development of motivational research. Even though the term has faded away, today's marketers employ techniques to analyze potential customers that hark back to the work of Ernest Richter, considered the "father" of this methodology, which probes for psychological factors that influence purchase choices. Like the old maxim of selling the sizzle, not the steak, automakers feel they must make the customer salivate and, most important, take action. Looking at questions of status and image, this chapter asks: Are you really what you drive?

Chapter 6: The Dealer Network

Enjoying their role as independent businessmen, many car dealers established reputations for honesty and fair dealing. Others gravitated toward dishonesty in an attempt to sell more cars. After World War II, a several-year shortage of new cars led to a glut. The answer was a flurry of hard-sell tactics. This "sales blitz" of 1953-54 resulted in federal intervention aimed at limiting certain extreme practices. This chapter investigates those hard-sell tactics, many of which survive into modern-day marketing.

By the 1930s, a separate automotive subculture had emerged, devoted to used cars that could provide additional use after disposal by their initial owners, whether as jalopies or "cream puffs." A glut of used cars forced automakers to re-evaluate their importance. Largely overlooked by the industry and media alike, used cars remain a vital part of the business revitalized by the emergence of Certified Pre-Owned programs, yet shadowed by shady selling tactics such as odometer rollbacks.

This chapter also observes, briefly, the development of manufacturing, starting when cars were essentially hand-built, assembled from components by small companies. Assembly lines were devised earlier, but used most effectively by Henry Ford for his Model T, which opened the way for mass production and distribution, and the beginnings of the automotive culture. After observing some of the thousands of companies that came and went over the years, we move into the postwar era, as the import brands move in and eventually challenge Detroit's Big Three.

Section III

Cultivating the Automotive Culture

Chapter 7: Historical Background - How We Eagerly Accepted the Car Culture

In the early days, automobiles were derided as "playthings for the rich." What Aldous Huxley later branded as "Fordism" began with the 1909 Model T Ford, which actually aimed at middle-class Americans more than the laboring class. Streamlining and style entered the automotive world during the Great Depression. Even in 1936, an astounding 54 percent of American families owned a car.

Pent-up demand after World War II led to 1950s dreamboats and the "horsepower race," as automobiles catered to the tastes of adolescents and young adults. This chapter looks at the full picture, through the import onslaught of the 1950s-60s, the "muscle car" era, street rods, sports cars, antiques and classics, fuel shortages in the 1970s - and then a rebirth of power and excitement as the 1990s approached.

Chapter 8: Installment Buying - Everybody Drives!

Growth of installment buying after World War II helped turn cars into "necessities." In the early days, cars were cash-only. Ford helped initiate the "No Money Down" economy with a primitive installment plan: paying for a car in full, week by week, before taking delivery. Time payments skyrocketed in the postwar period, as cars became harder to sell. Buying on credit quickly became an integral part of the suburban lifestyle. Before long, family financial turmoil and personal bankruptcies began to escalate. In recent times, an entire ancillary industry has emerged, catering to subprime customers: potential motorists who cannot obtain credit at ordinary rates.

Chapter 9: Gullible Youth and Perpetual Youths

Teenagers came into their own after World War II, as the driver's license turned into a rite of passage. Peer pressures made cars a virtual necessity for popularity, and the focus shifted to youth and excitement. As a result, young consumers were set up for a life of consumption and debt. Emphasis on youth also led to the push for power and performance, accompanied by high-risk driving, to the detriment of safety and environmental concerns. Consequently, today's roads are filled with middle-aged and older drivers who behave as if they were still 16 years old, exhibiting the "boy racer" mentality that drew them to brawny "muscle cars" or potent sports cars during their youth.

Chapter 10: More Than Transportation

Even before World War II, cars had become an integral element of courtship, sometimes derided as virtual "bedrooms on wheels." Young people, in particular, treated their cars as attention-getters and playthings. Hot rodding and customization reared their heads in the postwar years, letting young owners personalize their vehicles and also fill the coffers of the emerging aftermarket. Accessories are now an enormous part of the auto business, supplied by a largely separate aftermarket industry. Meanwhile, the recreational-vehicle industry emerged to create vehicles that could actually be lived in, though today, RVs have largely given way to SUVs and modified vans. All of these supplementary businesses helped to drive the car culture.

Chapter 11: The Car Culture Today

Drive-in movies and carhops might be close to extinction, but plenty of other automotive attractions continue to siphon off car owners' funds and keep the automobile culture rolling. Ads and commercials, even more than before, cultivate fantasies rather than tangible selling points. Also more than ever, many of them implicitly endorse aggressive driving. Motorsports, led by NASCAR, continues to build excitement for products by encouraging gullible men, in particular, that they too can drive like race-car pilots. Movies, TV programs and songs have promoted the auto culture for decades. Niches have arrived, such as off-roading, to cater to special-interest motoring.

Section IV

Motorists As Consumers: Are We Getting What We Really Want?

Chapter 12: Sorry, Drivers Are Part of the Problem

Despite the consumer movement over the past several decades, no one can keep us from craving those cars; and in too many cases, becoming veritable slaves to the automobile. Therefore, many of us buy the whole message, and are ready to defend the manufacturers and the auto culture against any criticism by consumer advocates or government officials. This chapter asks why so many of us have been that gullible, thus easily swayed by such tantalizing enticements as 0-60 mph acceleration times and steadily rising horsepower figures.

Yes, some folks maintain zero interest, seeing cars as mere appliances, despite the strongest efforts to persuade them otherwise. But for the most part, automobiles have a stranglehold on people's perspectives and behavior on the road. Because consumers face choices that are laid out for them by manufacturers and marketers, they're not entirely to blame for the negative aspects of the car culture. Still, if people didn't accept those "image" messages and turn them into sales, advertisers would face a far different task.

Chapter 13: Motoring Misbehavior

Ever since the imposition of the 55-mph speed limit in 1974, there's been an epidemic of violation of traffic laws. For a while, journalists and others even tried to suggest that disobeying the speed limits was a quasi-patriotic act. Some journalists continue to be part of the problem, not only by driving recklessly but even boasting of their illicit exploits to colleagues, and in print.

Because so many drivers see their cars as playthings, they're all too likely to disregard the welfare of other drivers and pedestrians. Everyone is in a hurry, it seems, ready to put themselves first. Despite hazy claims to the contrary, speed does kill, and it definitely burns more fuel. Furthermore, rude behavior, "me-firstism," lack of civility and incessant speed-law violations set the stage for comparable misbehavior in other aspects of everyday life. This chapter concludes with observations on drunk driving and the continuing prevalence of dangerous messages in auto ads.

Chapter 14: What's Next?

Most of us don't want to hear (or read) any criticism of the car culture. At least, not the kind that might compel us to give up or reduce use of our cherished automobiles. In terms of gullibility, we're not just sheep waiting to be shorn; no, we snuggle up and practically provide the shears with which to be "taken." As the domestic auto domestic industry in particular faces hard times, changes in consumer behavior and attitudes are inevitable. Yet, many motorists are sure to fight anything that could take away their prized "freedom" to drive whatever they like, as they wish.

Cars that park themselves already are on sale. Those that can drive themselves, on automated highways, are technically proven. Will Americans ever voluntarily give up driving their own cars? Probably not. Alternative fuels and the prospect for fuel-cell cars have captured attention, but unless gasoline prices shoot even further upward, the push for small vehicles and improved fuel economy may be short-lived.

Only an intense, long-term fuel shortage, of the sort that altered consumer behavior in 1973-74, seems certain to have a pervasive impact. Skyrocketing gasoline prices in mid-2008 yielded reduced driving, at least until those prices sank back down again that fall.

Meanwhile, highways are more crowded than ever, motorists are more tense and agitated, and a glance at any commuter-packed Interstate reveals that a lot of the pleasure has been taken out of driving. Yet, what would an American be without her or her own private automobile? Possibly, we really are what we drive.

Note: Outline will be updated to reflect current conditions.

Click here for an Overview of Steering Toward Oblivion.

Click here for an excerpt of Chapter 1.

Click here for an excerpt of Chapter 13.